Credit: DIY Perks

January 13, 2021

Every filmmaker wants to create realistic sunlight effects on their projects. Does this YouTuber have the answer?

Creating a realistic sunlight effect on a budget is the dream of many

independent filmmakers. While there are powerful units like 12K HMI’s

that larger productions use to mimic sunlight, they require a truck, a

generator, and a crew, and even then don’t always perfectly create that

special feeling of daylight.

This YouTuber, DIY Perks, has laid out a (somewhat) affordable system

for creating exceptionally realistic daylight. Intended for a winter

mood lift, he suggests this might also work for filmmakers. Will it?

Let’s find out.

First off, what he is proposing is broken into a few key steps.

1. Source a parabolic dish and line it with reflective tape.

So, the first step is to acquire a parabolic dish. This seems hard, but

it really isn’t; basically, every satellite dish in the history of

satellite TV will work.

You can find these used in a variety of online marketplaces for really

not much money at all. Since you don’t need it in working condition, you

really have your pick. Be sure to sand off any rust, since we want the

smoothest surface possible. If you don’t have a sander or room to work,

you can find dishes that aren’t rusty to begin with.

You then coat that with mirror tape to create a smooth surface. This is

again very inexpensive, and there are a host of options online.

It’s important to use tape instead of sheets since you are covering a

dish, not a flat surface, and that is more complicated. It’s easier with

tape to allow gentle overlapping and trim pieces to create a curved

surface.

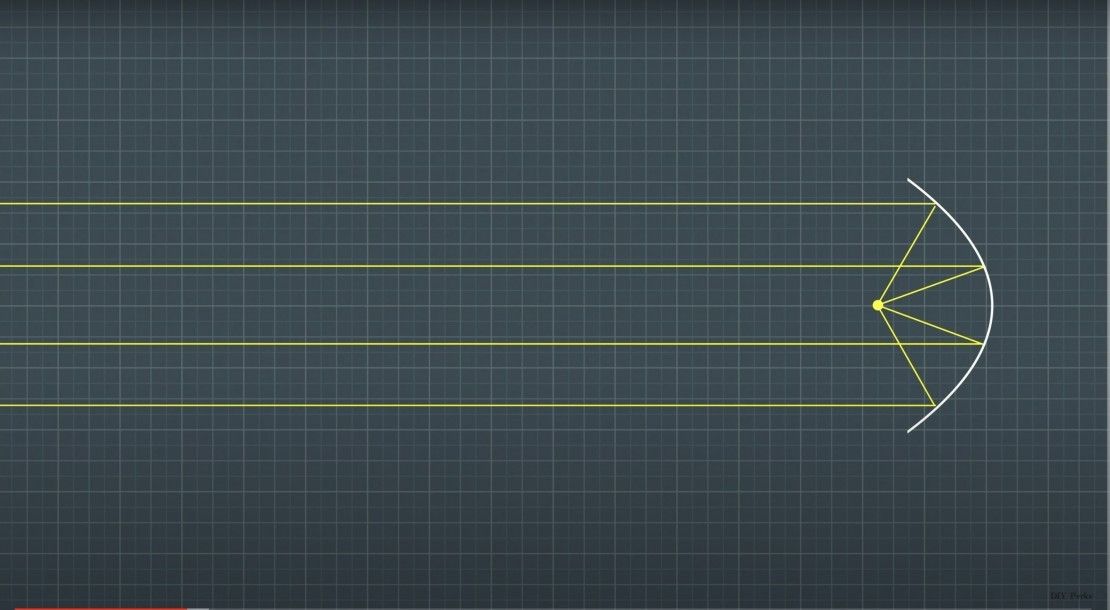

Why are you doing that? You are going to point a light towards it, and

that parabolic dish, which is now a mirror reflector, is going to

collimate the light so it runs more parallel.

Since the sun is millions of miles away, by the time its light gets to

us, it’s very close to parallel. When you are close to a light source,

its light radiates out in all directions. If you want to get your light

to feel like sunlight, you need it to be parallel.

The easiest way to check this is how much your shadow size changes when

you move closer to your shadow. If you stand outside on a sunny day, you

can move your hand to the ground and up to the top of your reach and

your shadow size won’t change much at all. Do the same with your lamp

inside and you’ll see your shadows change dramatically in size.

That has to do with how much “spread” there is in the light rays.

Collimating the light with the reflector makes them more parallel, and

closer to sunlight.

2. Mount an LED source to the dish

One of the nifty things about using a satellite dish is that it will

have an arm attached to it that is supposed to have a receiver at the

focal point of the parabola to receive the radio signal.

By taking off that receiver, if it’s even still there, and mounting a

light in that place instead, you can shine a light into the parabola

from the focal point, which should focus the light such that all the

light rays are traveling in parallel to each other.

In the video, this works amazingly well, and we have to admit it is

impressive to see how little shadow size change there is in the light

this unit creates.

We have to be honest, though, and say we would likely recommend

purchasing a prebuilt powerful LED to put in that position, maybe even

something that could be mounted into place. We could see bolting on a

Bowens or barn door mount to the dish arm to put a light there, though

remember, the dish is the heavier object, so you should mount that onto

the stand. If you try to hang a satellite dish off the front of a light

you are going to regret it.

3. Put a blue light scattering diffuser between the source and the subject.

Here is the real kicker. The sky is blue because of Rayleigh scattering,

which is a physical phenomenon that is a result of all the particles in

the air scattering the light as it goes through it. It makes the

sunlight feel yellower and the sky bluer.

It’s the reason why “sunlight” looks yellow to your eye if you look

towards the sun (don’t ever look right at the sun), and the sky around

it looks blue, even though daylight itself is 6500°K or even bluer.

To recreate that, DIY Perks builds a very nifty water tank that suspends

soap in it, using the soap particles to recreate a similar scattering

effect. Amazingly, shining the light through it really does look quite a

bit like sunlight.

So, will that work for filmmakers?

This first thing to remember is humans have a deep, instinctual

relationship with sunlight. Humans evolved for millions of years with

both sunlight (a far, blue source) and fire (a close, red source) as our

primary light sources, and it’s hard-wired into us to understand how

both work. One of the reasons bad lighting will often look bad is

because it’s trying to imitate a source but not doing it properly. It

causes deep instinctive bells and whistles to go off that tells us

something is wrong.

In one way, this is an amazing set of hacks for a filmmaker. By

analyzing all the important aspects of sunlight and mimicking them, it

should make recreating daylight scenes on a budget easier.

One key to remember is that light will still obey something like the

inverse square law (even lasers have some form of dropoff), where light

drops off faster the closer it is to the source, so we recommend placing

the units as far away from your scene as you can. The inverse square

law is why you can walk up a mountain and the light doesn’t get any

brighter, even though you are getting a mile closer to the sun; because

when you are that far away from the source it doesn’t change much.

But if you walk even 5 feet closer to a bedside lamp it goes much

brighter. Light drops off faster the closer you are to the unit. You’ll

need space to make this gag really work.

Where we think this might not work as well for filmmakers is in two

areas, both of which can be overcome in certain circumstances but need

to be thought about.

The first is flexibility. These home-built units just don’t seem durable

enough to continually pack up in your truck, drive to a set, and set

up. If you are building a permanent set in your garage for a YouTube

show and want to have a cool window effect, this could be an amazing

window effect to have shining through your window on a permanent basis.

But moving it around constantly doesn’t seem doable. It could be

interesting if someone wanted to make a direct to factor connection with

a satellite dish manufacturer and convert them to cinema-use builds

with robust mounts and connectors, but the DIY units won’t likely hold

up.

The second, bigger issue is coverage area. Because the light is

collimated, its coverage area will be relatively small. Parallel light

doesn’t spread, after all, making this very spotty. As you can see in

the video, it looks like you’ll need a unit for every single window.

Again, if you are building a permanent set installation we could totally

see putting this up on every window in a “set it and forget it”

fashion, but putting 20 of these on your truck in order to light even

the simplest of location shoots would be a lot of space on the truck.

I do remember in the 80s growing up with our neighbors (we lived in the

woods) having giant satellite dishes that must have been 8 feet across.

We haven’t seen those since the 90s, since satellite tech presumably got

better, but they must be out there somewhere. If one of those could be

purchased used, you could maybe get a pretty wide coverage area out of

it.

The blue light scattering diffuser is interesting since, at least in

this video, it does clearly affect the light in a way that most paper

diffusers just don’t. Again, for a permanent install, building something

like the aquarium system seems doable, but we would love to see

something more durable, with baby pins to put on a tripod, that we could

stick on the truck and bring with us to set. We would also love to see

more testing to see if there is anything non-liquid we could use to

create a similar effect. While we’re fellow users of black soap, dragging around tanks of liquid would be best avoided if possible, but maybe worth it if not.

We do think it’s a very cool idea, and honestly, we’re tempted to try it

for fun, using a movie light in place of building an LED from scratch.

If it takes off as a concept, we hope someone in the movie space will

make more flexible, reusable systems for both the parabolic reflector

and the blue light scattering diffuser.

As we head into the long winter months continuing to be trapped inside,

if we had space we’d want to build it just so we can have that “summer

morning breakfast” feeling instead of the “winter in a dark tunnel”

breakfast feeling we have as we eat our eggs before the sun comes up.

For that alone, we’re into this video.